Who Was The Woman Behind the New Deal?

- Jann Alexander

- Apr 20, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 21, 2025

And What Did It Take for Frances Perkins to Become America’s First Female Cabinet Member?

The only woman in the room, and the only individual to serve in FDR’s cabinet for his entire term, arrived for her job interview on February 22, 1933 with a very ambitious list.

In that 1933 interview, Frances Perkins outlined for President Roosevelt a set of policy priorities she would pursue: a 40-hour work week; a minimum wage; unemployment compensation; worker’s compensation; abolition of child labor; direct federal aid to the states for unemployment relief; Social Security; a program for young men to build parks, roads, and bridges; a revitalized federal employment service; and universal health insurance.

The hitch: Perkins would join his cabinet as Secretary of Labor only with FDR's agreement to enact her list of priorities. Fortunately for all Americans, he did, and we continue to benefit today from Perkins' list of policy reforms, all enacted in the New Deal under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. —J.A.

In today's guest post, N.J. Mastro, author of Solitary Walker and a historical biographer at her blog, Herstory Revisited, explains how Frances Perkins became know as 'The Woman Behind the New Deal.'

Frances Perkins: America’s First Female Cabinet Member

Guest Post by N.J. Mastro

In 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed Frances Perkins as his Secretary of Labor, making her the first woman in America to serve as a member of a president’s cabinet. During her twelve-year tenure as Secretary of Labor, Perkins would become the chief architect for FDR’s New Deal, helping to usher in a sweeping mix of economic, social, and political reforms aimed to improve the lives of Americans.

Times were hard when Perkins took over a corrupt and dysfunctional Labor Department. People were hungry and out of work as America tried to recover from the Great Depression. Adding insult to a broken economy, massive drought was strangling the Midwest and the Great Plains. In Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, and parts of Colorado and New Mexico, dust storms were wiping out entire portions of the state.

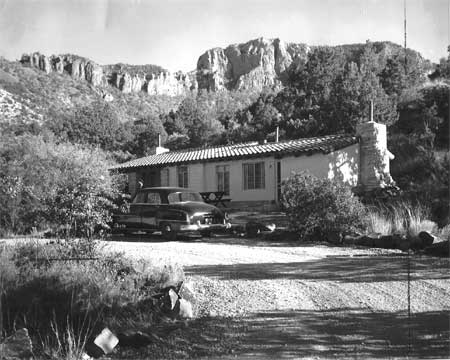

Big Bend National Park, Balmorhea State Park, and Palo Duro State Park became realities for Texans — as did many parks across the country — thanks to Frances Perkins' vision and rollout of the CCC

Yet Perkins would help change the landscape for American workers and families by championing scores of social programs Americans now take for granted. Among a lengthy list of initiatives, we can thank Frances Perkins for the following:

Putting an end to child labor,

Limiting the work week to 40 hours,

Creating a minimum wage,

Rolling out the Civilian Conservation Corps (the CCC), who built our state and national parks, and worked at conservation projects to improve forests and streamflow

Establishing unemployment insurance and worker’s compensation programs, and

Promoting a social insurance plan we now call Social Security, to protect the aged and disabled, as well as provide financial support to widowed women and orphaned children.

You read that right. We owe Social Security to Frances Perkins.

Perkins also oversaw the roll out of FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps, a joint effort between the Department of Labor, the Army, and the Departments of Interior and Agriculture to address unemployment. The CCC provided jobs for young, unmarried men while addressing natural resources, conservation, reforestation, and park development. Later on she rolled out the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, to further address unemployment. The WPA focused on construction projects that built roads, public buildings, bridges, parks, dams, and airports. Most of them still stand today.

Frances Perkins wasn’t your typical Washington politician. She’d been working in public policy and the nonprofit sector before becoming Secretary and had assumed a no-frills style: dark dresses, practical shoes, and austere hats, including a tricorn hat she often wore. Many were opposed to her appointment, yet FDR had seen what she could do. To keep the emphasis off her gender, Perkins did everything to avoid the attention shifting to her. She wanted to improve the lives of the American people. Period. She worked for them, not the other way around. Knowing she had to play by Washington, DC’s rules to get things done, when she had to, she drank and smoked with the men, her entry ticket to being part of “the club.” She gave as good as she got and went wherever the action took her, proving herself as a capable modern woman who could hold her own.

Perkins gave as good as she got and went wherever the action took her, proving herself as a capable modern woman who could hold her own.

For those interested in learning about Frances Perkins, Becoming Madame Secretary by Stephanie Dray tells Frances Perkins' fascinating story in fiction, from her start in public policy to her incredible rise in politics, as well as the private life she lived outside of the spotlight.

As the novel opens, after a prologue in which FDR and Perkins seal the deal for her to become Secretary of Labor, Perkins’ story shifts in Chapter One to New York in 1909, where 29-year-old Frances has taken up residence in Hell’s Kitchen. A graduate of Mount Holyoke, she is working on her master's degree in economics at the Wharton Business School. A summer fellowship has her collecting data on starving babies living in the tenements and settlement houses by measuring their stomachs.

Perkins descended from a long a line of patriots all the way back to before the American Revolution. She’s proud of her heritage, and her deep love for her country shines through. But she’s disenchanted with her country at present for not taking better care of its citizens. In Hell's Kitchen Frances encounters untold poverty, a movie she’s seen before after volunteering at Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago and working in the rough neighborhoods of Philadelphia, where she helped rescue girls from pimps and drug dealers.

She’s fired from her summer fellowship, however, for personally giving a mother money to feed her baby. The sudden change in Perkins’ fortunes is fortuitous. Florence Kelley, a well-known female economist and social activist who, a decade prior, founded the National Consumers League, hires Frances to help the League pass laws to limit factory work to 54 hours a week for women. At the time, workers were spending as much as 60 hours a week on the job. Perkins’ overarching question was, why not limit the length of the workweek for everyone?

Frances leans into her new role with gusto. But in 1911, when the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory goes up in flames in front of Frances in Washington Square, her personal commitment to ensure the safety of American workers through governmental reform takes on a new fervor. (There's much more to read with photos and documents to explore about the Triangle factory fire HERE.)

Three recent books look at the life and career of Frances Perkins

So begins the political career of Frances Perkins, told over the next three decades through Dray’s expert skills as a novelist. What drives Frances is anger over the way companies take advantage of workers, including children. Her work as a lobbyist takes her to New York’s state capital and eventually Washington, DC, where she makes her mark as Labor Secretary.

Frances Perkins was the only individual to serve in FDR’s cabinet for his entire term. Upon her retirement from public office, Perkins taught, wrote, and delivered public lectures. She died in 1965 at the age of eighty-five.

Women like Frances Perkins have been overlooked by history, making it imperative to take note of her accomplishments today. At a time when U.S. politics seems to be broken and politicians seem worried by little more than getting re-elected, we could use people like Perkins—honest, dedicated, and determined public servants willing to place the common good before personal ambition. —N.J. Mastro

Find out more about Frances Perkins by visiting the Frances Perkins Center.

Read N.J. Mastro's Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft for a page-turning historical biography of the original female trailblazer who now consider 'The Mother of Feminism.'

Learn about even more little-noted female trailblazers at N. J. Mastro's enlightening blog, Herstory Revisited.

Comments